February 2022 – Spatial Deconcentration

24 February 2022

By John C. Harris

Every community experiences change. Whether that change is imposed from the top down or generated from the grassroots levels depends largely on how power is distributed within the community. In the Lower East Side that power dynamic between city and community led to many confrontations of the two parties. Over the past fifty years the Lower East Side witnessed radical processes of transformation spawned by forces in the highest levels of power seeking to redefine the physical and cultural landscape of the neighborhood; real estate developers and the New York City government. However, it was not all a loss as the community was not without agency. Their efforts at collective action proved a catalyst for change which empowered residents of the Lower East Side. In this post we will explore the driving force of “spatial deconcentration” behind some of the biggest changes coming from the top down in the neighborhood.

The 1970s was a transformative decade for urban centers around the country and New York City in particular. Perhaps the most powerful process which defined that era is known as spatial deconcentration. The term was popularized by the work of Washington D.C. based housing advocate Yolanda Ward and heralded by activists like Frank Morales. Morales defines the concept as “ghetto dispersal,” or the depopulation of overcrowded urban centers in his zine The War for Living Space (available at the museum or here). In the zine, Morales uses carefully selected quotes from policy reports to reveal the process as a militarized effort to bolster white supremacy through housing policies that began in the 1960s. He applies this concept to the suggestion made by Anthony Downs in the “Future of Cities” chapter from the 1967 Kerner Commision Report to relocate Black urban populations. Whether Downs’ guidelines were rooted in the exploitative nature which Morales suggests, or he was sincere in his insistence on “a [housing] policy which combines ghetto enrichment with programs designed to encourage integration of substantial numbers of Negroes into the society outside the ghetto” because, as he noted, “most new employment opportunities are being created in suburbs and out lying areas,” the fact remains that his vision for communities like the Lower East Side was one that emphasized the dispersal of urban residents to the suburbs over resolving the sources of plight in crowded city neighborhoods. In other words he diverted his efforts from the root of the problems facing the residents of the Lower East Side when radical work may have instead created a more equitable solution for the community. Instead the nation’s, and city’s, commitment to Downs’ vision freed up space in urban centers for wealthy real estate developers to gentrify the former “ghettos.”

(The War for Living Space, MoRUS Zine Library)

So, what did spatial deconcentration look like in the Lower East Side? Perhaps former New York State Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan encapsulated it best with his phrase “benign neglect,” included in a memo he wrote while he served as counselor to President Nixon. Spatial deconcentration was in part fueled by the city government’s intentional disregard for systemic issues which plagued the most densely populated communities. The long term goal of that disregard was for the setting for a new social-economic scenario to present itself. What the New York City government ignored in the 1970s was the crumbling physical and social infrastructure resulting in part from a dual epidemic of arson and drug addiction in its poorest neighborhoods. The effects of this non-action were compounded by the city’s bankruptcy.

While the residents lived these experiences, academics have tried to pinpoint some of the exact issues in their research. While drug use in the Lower East Side is well documented the role of fire has long been considered as well. A 1980 report by Wallace and Wallace criticized in particular the joint project between the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Rand Corporation which put forth data models that justified the elimination of thirty five New York City firehouses between 1972 and 1976. This, according to the Wallaces, overwhelmed the Fire Department of New York and made it nearly impossible to halt the barrage of arson which seized neighborhoods like the Lower East Side. Rand responded in kind, complicating the story behind the 1970s fires.

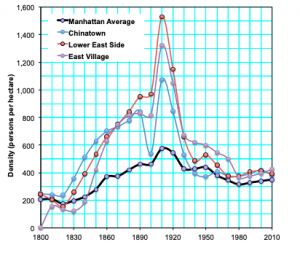

These processes ultimately led to an explosion of the homeless population and simultaneous shrinkage of the population in Lower East Side which inturn culminated in the residents migration out of the community. In effect Downs’ vision came to fruition. According to the Marron Institute of Urban Management, over the course of the 1970s and 80s the populations of the neighborhoods which encompass the greater Lower East Side (LES, East Village, Chinatown) dropped from roughly 550 persons per hectare to just under 400 persons per hectare. That’s a loss of nearly a quarter of the population. This video provides a year by year visualization of that population change.

(Population Decline in LES by Marron Institute of Urban Management)

When these social and physical transformations of the Lower East Side are scrutinized the city’s weaponized use of disregard for the community is clear. This systemic neglect was an affront on the community. The 70s were a decade of indifference with violent effects that reshaped the neighborhood, once bustling to the point of overcrowdedness and rich with character, to one that resembled a battlefield. All of these changes took place at the expense of those who, even before the process of spatial deconcentration began, were the most marginalized in the city. But the LES community did fight back. Factions of those who were able to stay, as well as some newcomers, forged an oppositional force to the city’s policies through grassroots action. They created dozens of community gardens and organized to rehabilitate their buildings and take ownership of their homes. They embarked on the collective journey that we now raise awareness of at MoRUS. Despite their best efforts, spatial deconcentration cleared the way for gentrification and the 1980s and 90s in the form of a crushing wave of neoliberal housing policy in the Lower East Side. The 1980s found the community once again primed for devastating change brought about from the top down. But the community was poised to respond. They had a decade of oppositional work in the 1970s to inform their work to reclaim and preserve their place within the neighborhood.